How a Water System in Ethiopia is Built

To successfully build a water system that supplies thousands with clean water in the rural highlands of Ethiopia, the thousands have to work together. In order to make it sustainable, they need to learn new skills. It also requires a simple but high feat of engineering, funds, and dedicated staff with the right expertise and experience to lead the operation. When all of this culminates, a water system is built.

The culmination largely happens because of dedicated HOPE Ethiopia staff, who live in the communities and work with the people, in order to help each project - each system and community - succeed. The on site team usually consists of Fetene, the water system engineer; community mobilizers, such as Ermias and Makades; and drivers, such as Merkam and Sisay. Each have an integral role to play throughout each project, which usually spans two years.

For the water system engineer, Fetene, the first few months are crunch time, as he designs the blue print for the system and launches the construction. In the Southern Highlands, fresh water springs are available on the mountain tops, and these are capped (protected) and formed into the water sources for the systems. Pipelines then draw the water down from the capped springs into large reservoir tanks, and from there the water is distributed to water points spread throughout the communities. This is the standard water supply system model in the highlands, but every mountain, every spring, is different, and Fetene needs to carefully consider the differing topographies as he designs each system. Who are his advisors? The local farmers, who understand the terrain best.

People in the highlands are excellent farmers, and their ability to work deftly and tirelessly in mountainous terrain makes it feasible to construct the system in such remote areas, for they are the ones to actually build it. Where there are no roads for vehicles to transport materials, the community dig dirt roads and carry the materials themselves. In the stead of modern construction machinery, they dig the pipelines that span kilometres across mountains. In this way, not only is the system constructed, but the community also takes full ownership of the system.

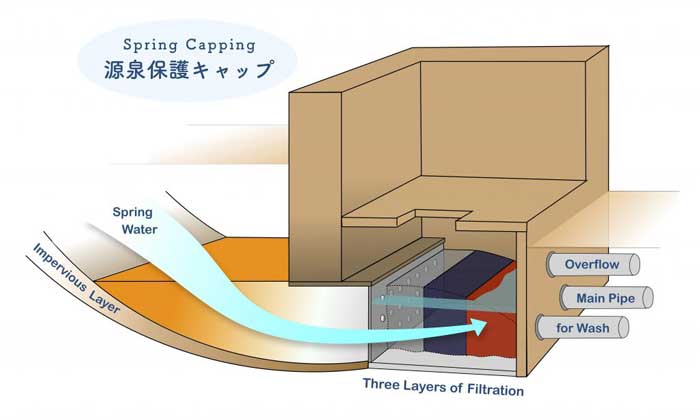

Spring Capping

When the springs are capped, 3 different filtration layers of sand are installed, to filter out any unwanted material that may contaminate the water.

They are also carefully sealed, to protect them from animals or playing children that may tamper with them. Three different pipelines are also connected to each spring: one that leads to the reservoir, one for overflow, and one that serves as an outlet for cleaning, when the spring is periodically cleaned.

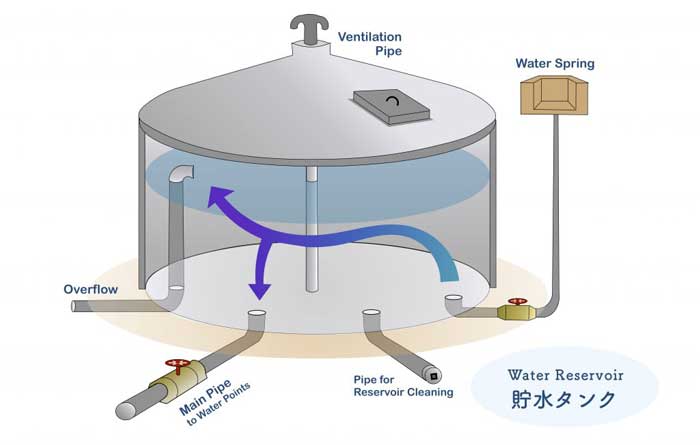

The Reservoir Tanks

The reservoirs are large tanks that collect the water from the springs and then distribute the water to the various water points. Depending on the number of water points and springs, the number of reservoirs can be as many as 3. The reservoirs are cleaned and the water is also treated with chlorine periodically here, and these tasks will eventually become the responsibility of the community to manage by themselves as well.

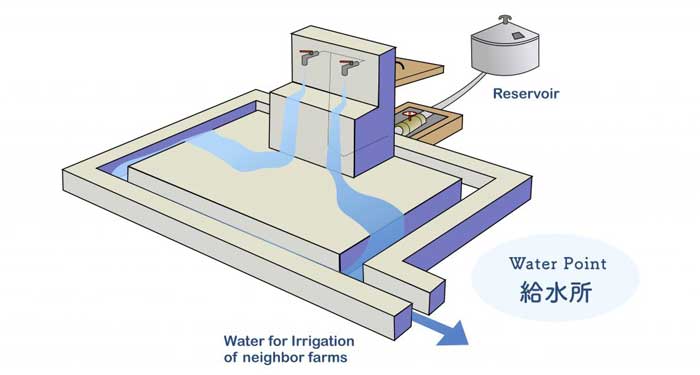

The Water Points

To make the clean water accessible to everyone within the community, the water points - where families can access the water - need to be strategically placed. Ensuring that each household be within 5 minutes walking distance of a water point is another important factor of the designing process, and Fetene, the community mobilisers and the community work together to determine where each one will be installed. While running tap water may still not be available in each home, for families who were used to walking kilometres each day to fetch water, this is a life change.

For the majority, no access to water and sanitation, also meant that their knowledge on hygiene and good sanitation practices were very limited. Reducing water related diseases and improving health overall, requires not only clean water, but also change in behaviour. The integral task of providing communities with this education rests on the shoulders of people like Ermias and Makades, who are the community mobilisers. From the start till the finish of the project, they live in the communities, learn their local languages where needed, build strong relationships with the people, and from there teach important practices such as hand washing and improved methods of household cleaning.

Finally, to ensure the sustainability of the systems, ownership of each system needs to be fully passed on to the communities. Selected members of each community are trained on how to fix the pipelines, clean the springs and the reservoir tanks. This they learn on the job, and as they learn, they also direct the construction of elements, such as the water points, themselves. For many, these are valuable skills that they had always aspired to learn, and they form what is known as the water system maintenance team. In addition to the maintenance team, water committees are also formed, and it is their responsibility to manage the various water points and collect funds from the community for any materials that may be required to repair the system in the future. HOPE always makes it a prerogative to ensure that women are also included as members of the water committees, which, for many communities, is another large shift in behaviour to have women in leadership positions in a predominantly patriarchical society.

HOPE staff and local communities work hand in hand for 2 years to build a water system, which is made possible by the donations of HOPE supporters around the world. In this regard, it is a truly global effort, to ensure that remote communities in the highlands of Ethiopia, have their fair share to clean water.

HOPE is currently implementing a Water Supply and Sanitation project in Kuta, where 4600 people are now on their way to receive clean water - March 2018.